Agentic Coding is a Fundamental Shift

coding is changed foreverpublished July 2025

Though I've spent the past few months writing about web frameworks and creative work, I'd like to shift gears and discuss AI. And more specifically, writing code with agentic AI through Claude Code1. Most people seem to have a tacit understanding that AI will have wide ramifications across all industries, but something is happening right now in the software world that's truly foundational, and I'd like to elucidate and explore it for those that aren't aware of it. This post gets technical at times, and tries to explain things from first principles at others, but I feel there is enough to glean for both coders and non-coders alike to make it worth your while. I'll discuss:

- What agentic coding is

- What makes "code" different than other forms of art

- How my work will change forever and what fears arise in that reality

- How people will "write" code they haven't read nor understand

- What responsibility do we have as engineers who secure systems

- What are some wider ramifications of this perspective shift

Though, I have more questions than answers.

I've spent roughly fifteen years writing software, am largely self-taught and have shipped a variety of personal and commercial software–ranging from consulting work, to free-and-open-source projects, to my own self-bootstrapped business. By any stretch of the definition, I've released both successful and unsuccessful work. That context is merely to explain that I've been around the block, and I have spent thousands of hours thinking about and writing software.

I've found myself largely distanced from AI, despite the wider industry fervor because I held a healthy skepticism–but Claude Code is such a vast step forward that it warrants discussion. Let's talk about why.

What is Agentic Coding?

Agentic coding is tool that allows you to prompt an "AI" to read code, write code, and interact with code. It can break a task into discrete steps and work on those steps one-by-one with little to no interaction.

Think about ChatGPT–you ask it a question, it gives you a response. But an agent is different–the agent can establish a list of tasks to accomplish, working on them one-by-one and prompt itself: using the output of the prior task to influence the future tasks. Instead of opening ChatGPT and asking it to write some code for you, Claude Code runs alongside your codebase. It can execute, test, run your code for you, and then feed the output (or errors) back to itself to inform its next steps, or resolve problems with the code it wrote.

It is a self-contained feedback loop that can keep working on a solution iteratively. It can fetch (curl) documentation from the web. It can run your tests for you. It is like having a little automated side-kick that's actually functional. And if you haven't used it, your brain might be flurrying to figure out all the reasons why this won't work, but I'd like you to suspend your disbelief for a second. There are some flaws and gotchas, so you're not wrong to be skeptical, but it does actually work. I had played with a few AI tools over the last few years, but relegated them to largely secondary or tertiary use-cases: bringing them in and out during long-tail coding sessions. But Claude Code is a more top-down approach. After a week working with Claude Code, I upgraded from the $20 plan to the $100 plan without thinking twice. It's that functional. If you prefer Cursor, Gemini, Codex, or another flavor of this product, that's okay–I personally didn't find the deep value that I'm talking about until Claude Code, but things are moving so quickly, the others may have already caught up.

To explain this, we need to go back and talk about what software and code really are.

What is Code?

I remember as a teenager being wholly confused about what software was. I downloaded a random repository from Sourceforge and stared at it, puzzled. It was just a folder. I thought "it can't just be a directory of text files that somehow unfolds into an app", but yeah that's mostly it. It can get a tad more complex; sometimes it includes assets (like images and videos) and dependencies (think shared pre-packaged pieces of code for common use-cases). But at the end of the day, software is largely a bunch of folders filled with text. And that's important, because it turns out LLMs are not just trained on "English", they can be trained on text of any kind.

For many, software isn't considered art–but it is a medium of creation nonetheless. For me, personally, it has always felt like an amalgam of art and functionality. But, software is a unique form of art, because its end-result (like a website or mobile app) is just a shadow of the work itself. The end-user does not see the code that you write at all. I call this "The Allegory of the Code". This disconnect is true of all art in some manner, you never see every component, but for painters you do see brush-strokes and colors, with chefs you can discern ingredients, musicians notes, and so on. There's often some distance between the act of creation2 and the art itself, but with code that boundary is somewhat uniquely rigid and distinct. So that's all to say, how one writes code has little attachment to quote-on-quote "integrity". Code is routinely shared, copy-and-pasted, inspired by others, and so on. There are licenses for open-source software that dictate what you can and can't borrow, but code is generally malleable and re-usable. Code is also private (downloading an app is not easily reversible to its original source code), so if you do something "unethical" (like actually stealing protected code from an prior company), there's often no way for anyone else to know. This is just the nature of the medium.

If an author writes a substantial part of their novel with AI, or a musician a song, we'd all feel a bit offended–and though that's part of a different conversation, we can find some tacit agreement about this. But with code there is no such truth, because we never get to see the actual work itself. All that really matters is: is the resulting software useful, thoughtful, beneficial in some way? Is it secure? How it's made is wholly abstracted away from its users. With the exception of open-source software, even software engineers don't know exactly how a product is made just by using it3. So while there is a philosophical discussion about ethics around training LLMs on code, I have found very few software engineers have the same qualms about writing code with LLMs. Something you wouldn't find in the novel-writing community for example.

Writing Code

For those that don't know, this is what code looks like:

As a program gets larger and more complex, it can split across many files, but at it's core, code (meaning, a program's instructions) is naively as simple as the text above. Just a file with some text that instruct the program on how to operate.

People think that software engineers spend all day writing code, but as most will attest, we spend the bulk of our days reading code and thinking about code. Because in order to write code, you have to take not one snippet above like the sum function, but dozens, hundreds of them, across many files and build a mental model of the software you are writing. You map out how the system works in your head and as you add features, or fix bugs, you re-organize the code to flexibly solve your problem. It's not so different from a crossword, you loosely internalize what clues are where and what squares are open. If you were to come into a half-finished crossword, it would take some time to build that mental model of what is already completed. The same is true for a software codebase.

And so what does it mean when an AI can roughly understand the mental model in seconds and then refactor your code to solve a problem, while taking into account your existing coding style and preferences? Allow me some patience for this absurd example: it's like writing a song, save for the third verse, and instructing the AI to write it for you based on the prior two–and, much to your surprise and perhaps dismay, AI getting it largely close to what you'd have written anyway. Except songs are not code–and code doesn't have the same visibility, nor pretense, as other artistic mediums. So it doesn't come with the same ick. And code has the ability to solve functional problems for people, through automation and interaction.

The first commercialized entrants into AI-driven code were useful, but I personally felt they were more cute and splashy than genuinely game-breaking shifts. Not so anymore, Claude Code represents a cosmic change because it can do more than just read and write code, or proffer bite-sized suggestions: it brilliantly runs from a programmer's terminal and can interact with your code and the outside world.

The Terminal

The terminal is what you might imagine "hackers" typing into, writing commands into a tiny box that looks like the matrix. It's what most software engineers use every day, not because it's cool (though it is), but because it's a beautifully simple interface for accomplishing a lot of tasks: like testing software during development, moving files around, or a litany of other tasks that we could never cover in totality here. Most things you do on a computer, you can do via the terminal in a more rudimentary manner. When you're working with data and software, it's more flexible than a visual user-interface because it is entirely text-based4.

Because Claude Code runs in the terminal, it can not only read our code, and write code for us, but it can interact with our code. It can run tests, execute our programs, and keep working until it finds a solution that works. It knows what commands to run, roughly. It can lookup documentation and gather knowledge. When a program fails, it can read the error and figure out what needs to be fixed. It is nearly as iterative as we humans are when it comes to writing code. Meaning you can send it off to accomplish some tasks and come back later to find it has written some code that works. I'm sanding over some edges here, it isn't quite as self-directed as I'm construing-but it's not entirely incorrect either. Other solutions like OpenAI's Codex are more hands off than Claude, and we're heading in that direction.

The New Workflow

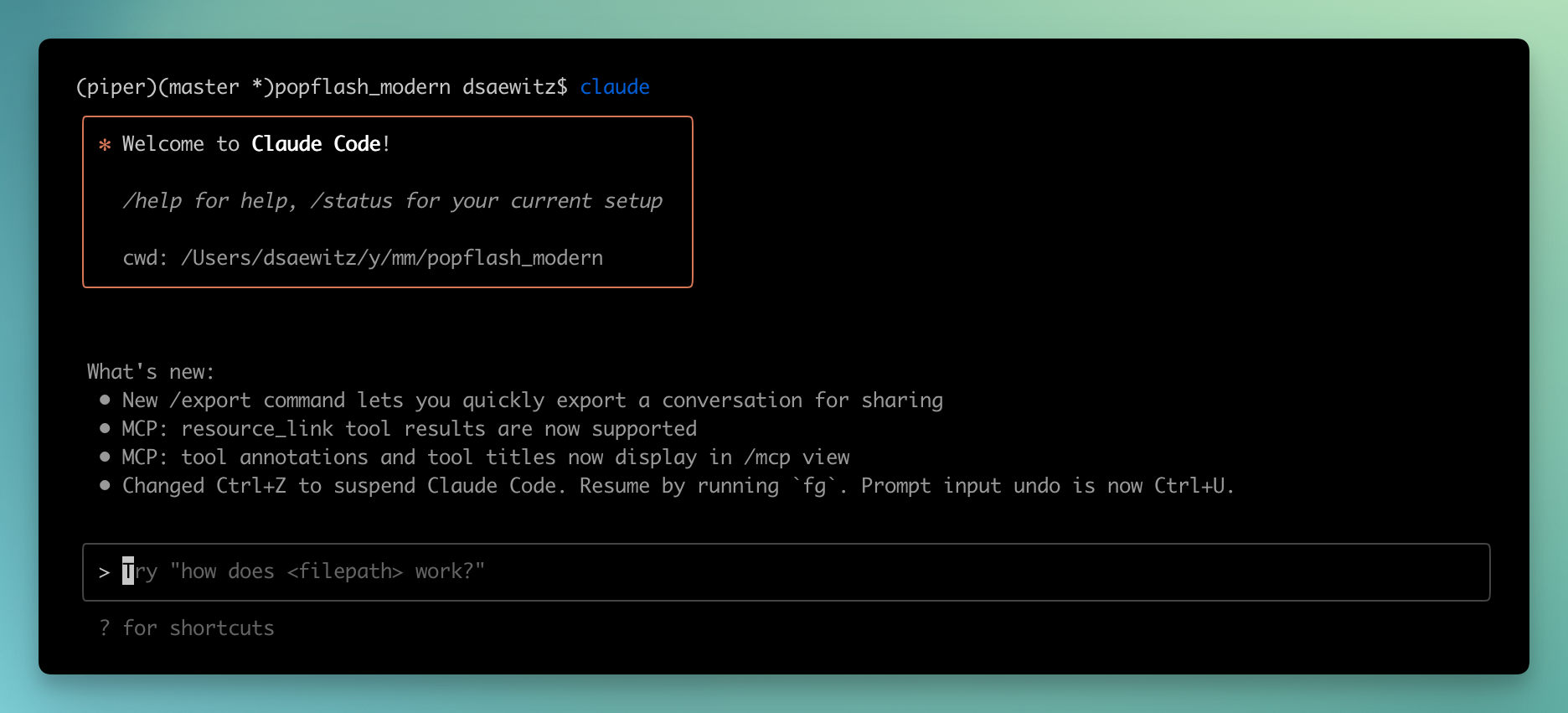

To use Claude Code you run the program in a directory of code (remember, it's just text!) and it is able to bring subsets of your code into context before composing a solution. You can then prompt it to engineer entire features that could have taken days or weeks in faster and more efficient time frames.

I recorded a video of me working with Claude to develop a newsletter form on my website. On the right you can see my codebase, with Claude Code running beneath it. On the left is my browser previewing the form.

The video is sped up 10x (53s) – but in eight minutes I engineer a feature that would have likely taken me 20 or 30 minutes before (or longer). It includes validation, client errors, half-decent styling, and submits your email to an external newsletter API. You could argue that as an expert, I could have done this all in eight minutes, but I'm skeptical of that and it wouldn't have been as comprehensive a solution.

It may be tough to discern what's happening here, but you can kind of see me flip between prompting Claude and modifying the code directly myself. Tossing the ball back-and-forth depending on what it is I want to accomplish, mixing and matching how I and the AI write code in concert.

Claude goes off and implements it poorly at first, but I can recognize that and redirect into writing the code closer to how I'd like to solve the problem. This moves quickly.

That isn't to say it's perfect. It's far from perfect, but in many cases it is also good enough. And there are situations where it can solve complex engineering tasks that would have taken weeks in just hours–and write code similar to that of any engineer. This isn't "vibe-coding", where you end up with a Fantasia-style mess, sending a bunch of magic-brooms to fill up buckets of water which end up out of control and flooding the system. Claude Code could drive you down that path, but it's far more nuanced and wrangle-able than the prior "vibe-coding" solutions. Something that can actually be wielded by thoughtful engineers. The reality is, it's so powerful and performant that once you start using it, you will see how rarely one would write 100% hand-written code ever again. Our work will never be the same.

Sometimes it hallucinates, sometimes it writes bad code, and sometimes it breaks. But sometimes it writes even better code than you would have written, sometimes it sees a problem and designs more elegant data structures, provides you with some esoteric knowledge that even you as an almost two-decade veteran don't have yet, or forgot about. And this is what's actually happening today, chances are the UX will get smoother, the solutions more comprehensive. Claude Code is so fundamentally shifting that I'm fairly certain our industry will never be the same. This does not mean we won't need software engineers anymore, but I believe our role is going to fundamentally shift from building up massive pillars of esoteric knowledge to one being closer to a sheep herder of code and instructions. Like conductors of orchestras with infinite stamina, infinite knowledge, and little expertise. We will bring the expertise and the automated agents will go off and do most of the busy-work. Rather than imagining a future where we do nothing and they do everything, I see it more as a yin-and-yang, a back-and-forth throwing of the ball, working in concert together.

You might mistake me for an acolyte of AI, but there's a reason I spent the last two years writing blog posts about things completely unrelated to AI. It's because until Claude Code, I found AI useful, but not nearly as fundamental. It's fundamental now, it's here. I'll still write code by hand often, but I don't think I'll be writing exclusively hand-written code nearly as often–especially for smaller, more contained stuff.

What Knowledge is Authentically Rooted?

Most people understand that there are different programming languages, but they don't necessarily understand what that means. For example, do you understand the distinction between a language like Python and CSS? Many engineers wouldn't even call CSS a language–because it is not as much a programming language as it is a "specification" for designing web layouts. In five year old parlance: it makes boxes on websites blue and red.

CSS is the visual design language of the web. You don't write programs with it, but it is code. And so understanding it is less about raw math and logic and control flow and data structures, as it is investing thousands of hours to understand how it works and untangle its quirks. Those who have put in the time to master it are often referred to as "css wizards", because its knowledge is less rigidly fundamental and more incidental. In many ways, it was a wonderful gatekeeper of job security5, because it was hard to understand and took genuine effort.

But if AI can come along and get you 90% of the way there without the pain, is there value in truly learning it? Was it ever valuable? Was it just a magical incantation that we spoke to accomplish tasks and bank high-income jobs. Will future developers deeply understand CSS or will they just instruct an agent to move a box over three pixels? I may manifest as the dusty guy in the corner of the bar muttering about how the kids these days don't understand css floats. As we well know, you can't trade off experience. And at some point, an inexperienced race-car driver who is speeding will crash off-track. And by crash off-track, I don't mean that they will break their codebase. I mean many people will ship code that they:

- haven't read

- don't understand

- is littered with bugs and security holes

But also those people will build things that they weren't able to before. Code will no longer be looked at as a secret language for the nerds–we are about to see an influx of people "coding" for the first time. It's actually already happening if you're paying attention.

I'm less concerned about those of us who are experts–because we will still be needed to untangle the messes created by inexperienced people wielding these tools. They are not a silver bullet, and it's blatantly clear to me how often Claude Code writes bad code. The thing is, I can identify when that happens and redirect it into writing pretty good code, because of my expertise and knowledge. We are not in the matrix, and having all of the knowledge at our fingertips does not mean we have internalized all that knowledge. And even though things change quickly, I don't think tomorrow this means we are all out of a job. Though who knows where we'll be in a decade. We could end up with more coding jobs as there is more code being written. An easy prediction is that the number of lines of code written globally going forward will hockey-stick. We haven't even scratched the surface.

If you gave me Claude Code twenty years ago, I would have progressed at lightning speed, but I also wouldn't necessarily have internalized all the lessons that I have. And I think ultimately, I'd be both further ahead and further behind. I'm not here to cast a judgement on that. At the end of the day, I don't really care. Because I enjoyed writing code and I enjoyed solving problems. For some, this will suck all the joy out of programming, and for others this will make programming remarkably fun. Ultimately, we're going to see the hipster purists who only write authentically hand-written, organic free-range code and the vibe-coders speeding off track, leaking all your data in the process. The rest of us are going to land somewhere in the middle, working with AI agents to write code–just another tool in the toolkit, even as transformational as this one is. These are the same questions that people were forced to confront at the precipice of prior technological revolutions. In Moneyball terms–"adapt or die".

The problems I foresee is that the people with the most velocity will be the ones with the least expertise. They can now wield and build behemoths of complex software with few walls, which sounds wonderfully democratic until you realize that software engineers hold some level of responsibility. We don't quite hold the same weight as a civil engineer designing a bridge, but we still are engineers of some kind, responsible for people's data and privacy. And those of us who have reflected deeply upon learning how to code, brings with it a weight of respect and responsibility. If it takes little effort to write code, the opportunists will come to pillage with no regard for their users' ethical concerns. You could argue we as an industry have already failed at that, but I surmise it's nowhere near as bad as it could be.

Personally, I've watched AI write a number of security holes without realizing it. I've watched it write shoddy code that is brittle. And so again, I'm not here to make a judgement, but I think we're going to see a wild explosion of new software, and also software that is bug-ridden, insecure, and problematic.

What's most exciting to me are the craftspeople, the independent developers who will be able to create genuine, authentic experiences using their expertise to move a heck of a lot faster. Those of us who care, who invest immense time and thought and intention behind our work, will use Claude Code as a tool, rather than a lifestyle. We will intersperse hand-writing code with automation. We will use it to finally write tests for our software. We will be able to move in small teams as fast as some large teams were able to in the past. And for you, the consumer, you will end up with better and more personalized software. I don't want that to sound clinical–perhaps it is–but I naively believe good software can be very humanizing. I think we sometimes worry about the perverse effects of technology, rather than its magic. It's both things. I'd implore you to try and accept the duality here.

Funny Side Effects

Claude Code right now is severely subsidized. You get thousands upon thousands of dollars of utility value (meaning, not the value of the output but the actual cost to Claude to provide this tool) for a mere $20, $100, or $200. This much seems clear. So you may say, there may come a time in which the financial cost of writing code this way is unsustainable. But I think over-time this cost cheapens aggressively. And stuff like this usually approaches relative-zero rather quickly. In the meantime, it's pennies today.

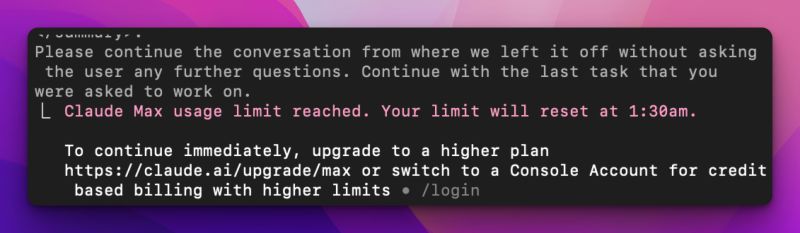

Claude's way of limiting your abuse is to allow you to do a certain amount of work in windows of time. So after a heavy two hour session, Claude may tell you that you have to wait an hour until 5PM EST to continue working. Sometimes you're so mid work-stream that untangling your current working AI context-mess manually is not worth the effort and you say, "welp I might as well wait an hour or two" (or upgrade to a slightly higher plan). It's almost like a forced limiting function, a forced pomodoro-timer. So you get up and take a walk, go work on something else, or just wait it out. It's odd, and feels wholly unnatural to be told by an AI that you have to take a break. But I've also found it to be not that dramatic. I probably don't take enough breaks when I find myself in flow–and taking an hour here or there hasn't felt all that punishing when you're moving so fast.

Naive Projections

Writing code with agentic AIs is remarkably similar to working with very prolific junior engineers. If a junior engineer deletes production data – who's at fault? The senior engineer who even made that possible. The same strikes me as true here. We're going to have to build security into our systems a level above our code. So things like row-level-security in a database, which make it somewhat impossible to leak data to the wrong user will become more common-place. These are things we should be doing already, but most engineers don't.

I believe code will become looked upon as cheaper (but not holistically worthless). Many senior engineers have been espousing for a long time that code has less value than the emotional value we put on it–and I think that only becomes more true as writing code is something that can be automated away.

End-users will begin to write code without realizing it. They'll talk to a system or application in plain english and in the background, code will be generated from their prompts. This will be largely invisible to them but will open up automation not possibly realized before.

Rigid building blocks will become all the more important, like strong cloud data primitives that are tightly integrated into code. Cloudflare workers' employees have been hammering the point home for years how durable objects, queues, sqlite (d1), object stores (r2) are these incredible data primitives that can be mixed and matched like legos, and I think as the code around services becomes more brittle (or potentially brittle), we'll want more rigidity around our data-structures using off the shelf tools. We write code because it is so flexible, but the less code we have to write, the better. Especially around I/O and data patterns. I expect a lot of inspiration here to come from unix tools and pipes.

Monorepos have already become very popular, but they will be even more popular as agentic coding desires to read and write code across services.

Ramifications

So is this good? That's the question everyone seems to ask me. I'm naive, but not naive enough to declare some binary future outcome from this. It just feels rather inevitable. It doesn't matter if it's "good" or not, or if that would even be a measurable metric, because we have no way of stopping it–it is such a massive shift forward, and with that comes the bad and the good. I've seen people compare it to prior computer science innovations like higher-level languages, but I think this is different. This is its own thing. You can either embrace it or stick to "old fashioned", "hand-made"-techniques. Some will use it well and some will use it poorly: any nuance beyond that is above my pay grade.

Do I hold fear that this may be the end of my job as I know it, or that my art-form is radically changing forever, that all the time I invested in learning its nuances are now "wasted"? Only at a surface level. I enjoy writing code and I enjoy building software. But only my ego believes I should be the only one to have access to writing code, or that my sweat and effort gives me license that others don't get. It's somewhat contradictory to be an advocate for people learning how to code, and then feel cheated because the barrier to entry has been lowered tremendously. Coding has always been this black-box to outsiders, but I have long proffered that it's not all that different from learning guitar or any other complex skill. It's just newer. Most people can't play guitar, but they're not so intimidated to learn how to play a G-chord. Coding will become more accessible to the outside.

It's important to emphasize just how much this lowers the barrier to entry. I have several friends who never wrote code before AI, who are now building full-featured apps. Just copy-and-pasting from ChatGPT was enough to get them hooked, and they've all switched to Claude Code. They're creating real software. If you poke around, you'll find this story to be popping up more and more. Claude directs them when they don't understand something–no more diving into esoteric StackOverflow threads with little direction. You don't have to know how to install node modules, or run a script, or anything. Claude will guide you. And these tools are only going to lower the barrier further.

A few years ago, I had built a truly complex piece of software. It was a niche product, a 3D-rendered game engine for esports analysis. It was so powerful that just a teaser demo of it got hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube and placed me at a high-priced steakhouse in midtown new york city, sitting across from a business executive whose CTO told him he should meet with me and consider acquiring it. After a long conversation, it was clear this executive had absolutely no clue what my software did and when I challenged him on it, he snarked back at me that he could "hire a bunch of engineers in Russia for cheap" (his words) to build what we had. I chuckled: he had no understanding of the earnest complexity of what we had built and I politely directed the rest of the conversation to pleasantries. They never built what we had, and as far as I know, their company never found product market fit. But I'm not sure I believe the same sentiment anymore–we're about to enter a phase of rapid democratization of software creation. Complexity will still exist, but the barrier to entry has been made so low in a way that most old-hat software engineers don't seem to fully comprehend yet–or don't want to.

All of the same fears, insecurities, concerns of other rapid changes in technological innovation can be applied here. And several further. For one, code itself represents exponential complexity – and when we wrote it by hand, we had far more oversight over it's effect and scope. But now software engineers are going to ship a lot of code that they themselves do not understand. And when you're talking about securing people's data, or other important software, we are going to experience failure on a major scale. Security may get worse, user experience will experience flashes of both improvement and failure, as we ship more powerful code that is also more brittle. Even for those of us with deep experience and a commitment craftsmanship, we will all move faster than ever, but at some cost.

On one hand, we are democratizing knowledge and creation, allowing more people to wield automation. But on the other hand, all of that institutional knowledge acted as a security gate, creating a somewhat-healthy limiter to those who could build software. In the words of The Incredibles: "When everyone is a superhero, no one is". Again, I'd implore you not to succumb to binary thinking here, that this is a wholly bad or good outcome. It's a wild concoction of both. It just is. And it's currently happening. This isn't nihilism, this is just an understanding that this is all math, and math is inevitable–it can't be secured or contained any more than cryptography can be controlled. Change is constant. We can either embrace it or reject it. It's both more and less dramatic than we might think. And as always, we'll try and figure out ways to work with it. I don't want to make sweeping projections about the future, I just want to give you a slight window into what is currently going on in my field, and the way it may change others. It's worth knowing.